Donald Lang only visited his wife on Tuesdays and Fridays. And like every Tuesday and Friday he was done up for it – a wax cotton jacket over a check shirt; tie a neat Windsor knot. His corduroy trousers ended where his stout shoes started. He wore a flat cap.

As the ferry approached the quay he thrust his hands into his jacket pockets. A wicked wind blew up the Tay and made his face glow red, he’d be glad of the shelter in the city. One pocket bulged more than the other – he always brought the same offering for her. They were in a paper bag and his hand wrapped around them. Finding a sharp edge, he squeezed more and felt a jolt of pain and a soft snap. He stopped before drawing blood.

He disembarked and touched his cap at Alan who worked the hawsers. Foot passengers were allowed off first. Then off rolled the carts, the marmalade wagons, coaches and a clutch of motorcars, some two-wheelers. A Rolls Royce. Livestock last. Since the War Donald had become a part-owner of the Newport-Dundee ferry. All he did was attend a meeting once a month to make sure ticket prices were in line with profits. He was aware of the inequality in his city: Three shillings was quite enough for a single passage. Greedy the likes of Queensferry who charged ten!

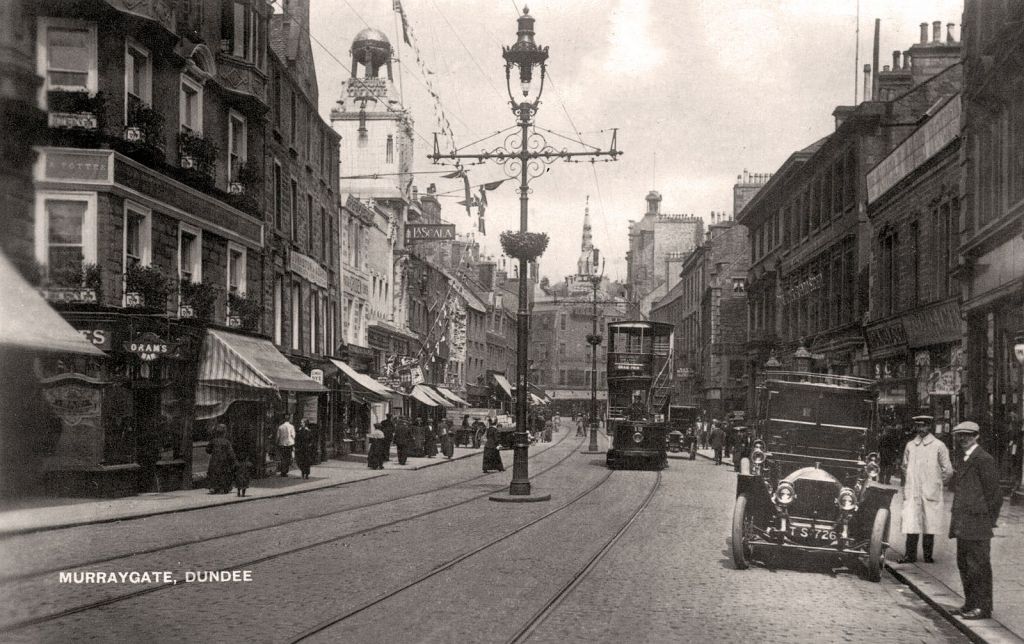

He took the route he always did, striking up the lane alongside Caird’s new hall. He folded up his collar when he turned onto the bustle of the Nethergate. Crisp air shot from the East and marshalled clouds of smoke away – giving snatches of clean air, a rare thing in the city. The sound of wood and iron clattered along the stone setts. Bundles of newspapers thudded onto waiting carts and linen was being flapped and folded into crates.

He walked this way because he passed St Paul’s Kirk where they’d first met. He squeezed the bag again, it was wet by now and he felt it tear.

Just past the Kirk he waited at the kerbside. A lad stood next to him, his bare feet black as soot. Both their heads followed the Rolls Royce prowling past, up towards the factories. It was the same one he’d seen at the ferry, its top-hatted passenger taking advantage of Dundee’s cheap labour. When it passed, the lad’s gaze shifted up to Donald, a cupped palm stretched towards him. Another car stuttered past and Donald looked up and down for another, before placing one from the bag in the lad’s hand. There’d been recent incidents of pedestrians hit by motorcars. He’d survived Ypres; he didn’t want to end it under the fender of a Ford. There were none, so he crossed, hearing the padding of the wee lad behind, feeling in a distant way the lad’s disappointment at what he’d put in his palm.

The Nethergate became Perth Road. Around him the dim thuds of commerce and diversion. He looked forward to Tuesdays and Fridays. That is, to visiting her. Not just because it gave him a sense of routine but because he could relive their past. They’d laugh about the time he left their holiday cottage in St Andrews rod in hand, confidently proclaiming he’d be back within the hour with supper. He’d returned the following morning with nothing but a runny nose and an empty bait tin. Later, she’d come with him to France in the early days of the War. They had a farm cottage, and she’d gather eggs and wine. He’d stroll up that muddy track to the cottage to find a spread on the table – her in pinafore, wiping his glass and filling it as he sat. He’d bathe after – often his face was muddy. Often too it was bloody.

He liked the idea of the Perth Road. The idea that if he followed the road he’d eventually reach distant Perth. As a schoolboy he’d overcome the fear with his pal Ally – they’d cycled until road’s end. Arriving victorious, the world suddenly seemed manageable. If they could make it to Perth then why not Peebles, Plymouth, Paris? Manageable that was until they had to cycle back and couldn’t, sleeping in a field outside Kinfauns and arriving home filthy and shivering. It had taught him a valuable lesson: planning. Planning was to an army officer what jute was to a mill.

She’d run a tight ship in that farm cottage. It was near the Front; shells boomed. Sometimes the ceiling shook and plaster dusted their soup. He’d wake and splash his face with water and report to the front at 8, then return at 6 to steamed windows and the smell of boiled cabbage. After dinner and after a bathe she’d light candles and busy around him while he read. He’d look up from his book and watch her; making sure there were enough logs about the hearth, running a duster along the mantel, eventually settling on the couch with a magazine. He’d move next to her and they’d sit a while reading, the crackle of the fire, the occasional distant boom, the languid tat-tat of machine gun fire. The drone of a bomber. It couldn’t last. They’d been in that farm cottage six weeks when life and any hope of victory ended.

He passed St John’s on Perth Road, studiously avoiding the stained-glass gaze of Knox and Calvin. Above, its spire like a gothic rocket pointed to the sky, a spectrum of grey, clouded and busy then, a crack of blue. A fine time of year to stroll, the clip of a heel, the crunch of leaves, the evenings closing in, a long evening by the fire with a book. Again, he squeezed the bag in his pocket. That’s what had gotten him through days in the trenches. The thought of victory. Victory was those evenings they spent together by the fire.

But victory was the other side of the line, something ‘over there’ beyond ‘this’. The suffering. The best was when the bullet entered clean through the brain and there was no squirming. He’d spoken with a Private from Cupar, he’d said about their cottage in St Andrews, turns out the lad’s family worked as caddies on the Old Course. Donald assumed it was the Old Course because his mouth was the shape of an O when the bullet entered it. The laddie stood a moment, the bullet having sailed through him without hindrance. His mouth was still an O, face caked with a fond memory, crumpled on the muddy trench floor.

Not long after, he was walking back up the track to the cottage. No light inside. There wasn’t the bark of the dogs. The front door was ajar. He drew his pistol and edged in. Neat, orderly, like she always kept it. A lone dinner plate was on the kitchen table, she usually set them at lunch time. For their evening together. The other was in pieces on the hard floor.

Soon after he had leave. He wanted to stay but he was ordered onto a ship to England. The enemy had cleaned out the farm cottages; he was lucky not to have been ambushed. The bodies of the farmers were found nearby. Hers couldn’t be located.

He’d move to the trenches and stay there. But first, two weeks in an officers’ mess near Southampton. He went with Peters, a shepherd from Cumbria. They were billeted next door to each other –Royal Engineers like him -.in rooms with large beds and balconies. He didn’t rest. At the Front it was their weapons that were letting them down. Young lads were getting mown down on every advance. Only their numbers, buttressed by men from distant colonies, allowed them to hold their position. Half the time they’d hardly chink the mighty enemy armour. They needed proper planning. They needed decent weapons. He knocked on Peters’s door and they started scribbling. Their ineffective weapons, tactics, planning were causing the deaths of children, allowing wives to be murdered, sending men insane. Scribbling more, working late, always a bottle of whisky with its cap off. Before the end of their leave Donald and Peters were in their Number Ones in front of General Hough.

Donald presented the idea. Devastatingly simple. A mortar which would launch canisters of flaming petrol up and into enemy lines. They’d explode and engulf the swine in flames. Burn the bastards to death. General Hough smiled a toothy grin and said there was a budget for ‘this type of thing’.

Donald smiled too. So did Peters. A few days later they heard the news that their new hardware was going into production. They went to a public house and got wild drunk. General Hough said it would be called the Lang Projector, after Donald. It was a scant couple of weeks before the first one was lashed down to HMS Vengeance and then wheeled along the trenches one morning, its wheels squeaking with the birdsong. No time for testing. The men were given a short briefing, by Donald, and he stood back in the shadows as the first canister screamed into the air. He watched its hideous beauty – shape like a pine cone, it seemed unsuited to flight. But it belched through the air against nature. And it landed where it should. He raised his tin helmet just far enough above the parapet to watch grey uniforms running like ants on fire. For you my love.

He remembered nothing of the night in the public house with Peters except one thing. At the end of it, when Peters was too drunk to hold his head up and all the other drinkers had left, the barman was wiping glasses. Donald leant in to Peters, threw an arm around him, his breath sour with drink, ‘every fucking missile that that thing launches is a judgement, a judgement on the enemy, for taking her.’ He’d sobered up a moment, as if he’d said something poetic and should write it down. Then fallen off the bar stool and been carried home.

He watched as the men got excited by the new toy of death, loaded another heavy pine cone canister brimming with petrol and launched it: clank, whoosh…bang! Then another, another, another. Soon they were rolled out across the Western Front. Thousands of strikes were credited with the Lang Projector. Waves of flames swept the enemy from their filthy sties, carried them to the hell they deserved. They denied him victory – he’d deny them life. It killed thousands. They gave him a medal.

When the bloody thing was over, he was just another set of limbs in a French port. He carried a wound in his right eye but he’d been lucky. A writhing mass of humanity trying to get on a boat to the white cliffs of England. Civilians. French. Who knows? Maybe the enemy. Everyone was too tired to care any more. Donald reached the front of a line and picked up a pen to sign a ledger but his hands shook too much to write. The other entries were scrawls of lines. Trench hand. The pen dropped onto the ledger with a dull thud. Only one word was comprehensible on the two pages. A name. A cruel coincidence: Her name.

‘Donald.’

He turned and she was there. It wasn’t a coincidence. It was her. She was leaner, not emaciated. Healthy. Hearty. He knew the suitcase which sat at her feet. She wore the dress she would have been wearing when he arrived that night. It was clean, unstained.

‘Donald,’ she said again.

He drew a quivering face to hers. A familiar scent of powder on her cheeks. He snapped back and asked her, point-blank, shaking. She told him how they’d taken her prisoner but kept her so well she felt as if on holiday. Fresh mountain air, music classes, assurances of being released as soon as possible. Decent people, she said. Decent.

He looked at her face, light with gratitude. Decent people. Clank, whoosh… bang! He pointed a muddy and cut finger at her. Then he placed his hand on her shoulder which steadied it but stained her.

‘Donald?’

He was outside the Howff now. A corps of headstones lined up: hers was half-way up on the right. It was a simple one – and a handsome one. He’d paid for it, planned it to make it just right. The base of it was almost engulfed now, the pine cones obscuring her name. He’d lay one for each of the lives his projector had taken. Ill-founded ill-will. It would take a lot of visits. He slapped his palm on the headstone to steady it, steady himself, then took the bag of pine cones from his pocket. They scattered around the stone, the pile already high. It was a mountain sure enough; it was mountain. He did an about turn back to the ferry, folding the ripped and bloodied paper bag into his pocket.

The Lang Projector appeared in an anthology of short stories about Dundee, The Low Road (2021) which is available at Waterstones, among other outlets. https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-low-road/nethergate-writers/fraser-malaney/9781838436506

Leave a comment